Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure and Change Macrosociology: Four Modern Theorists A Commentary on Malthus" 1798 Essay as Social Theory Great Classical Social Theorists In the Classical Tradition: Modern Social Theorists Dr. Elwell's Professional Page

|

rbert Spencer's Evolutionary

Sociology Jared Diamond | |

|

The Implicit Ecological-Evolutionary Theory of Jared Diamond By Frank W. Elwell An excerpt from Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure and Change

Diamond is a public intellectual who has made social evolution accessible to a broad public; while he is not a social theorist his work is very consistent with ecological-evolutionary theory as developed by Gerhard Lenski and Marvin Harris among others. While noting that Diamond does not label his analysis as ecological-evolutionary theory, Gerhard Lenski (2005) states that “most of the chapters in Guns, Germs, and Steel provide valuable further tests of the principles on which ecological-evolutionary theory is based” (145).

Diamond posits that characteristics of the environment—physical,

biological, and social—play a dominant role in sociocultural stability

and change in human societies. What he demonstrates is that these

environmental characteristics largely condition what is possible in

production and population, and that these environmental and

infrastructural factors combined affect not only individual

sociocultural systems, but the world-system of societies as well.

Diamond first focuses on what he calls “ultimate factors” in explaining

the vast differences in social development among societies. These

ultimate factors are all environmental in nature: geography, soil

fertility, plant and animal availability, and climate.

Other factors that lead to inequalities between societies according to Diamond—population, production, social organization, ideologies—all come into play in his analysis as “proximate causes,” strongly influenced (if not determined) by environmental “ultimate factors.” But the differences are ones of semantics: the social scientists and the biologist all begin with environmental-infrastructural relationships and focus upon how these factors profoundly affect the rest of the sociocultural system. How then does Diamond explain the great inequalities between sociocultural systems in the modern world? What explains the patterns of wealth and poverty we see between societies?

Jared Diamond’s short answer to these questions is that the speed and

course of sociocultural development is determined by the physical,

biological, and social environment of that system (25). It

is to a slightly longer version of Diamond’s answer, specifically how

these factors are directly related to population size and density,

division of

labor,

and technological development, that we now turn. About 10 thousand years

ago according to Diamond, agriculture originated independently in five

areas of the world: the Near East (or the Fertile Crescent), China,

Mesoamerica, the Andes, and the eastern United States.

While there are several other areas that are candidates for this

distinction, in these five areas the evidence for independent

development is overwhelming (98). Most other areas developed agriculture

as a result of diffusion from other societies, or through the invasion

of farmers or herders. Others failed to acquire agriculture until modern

times. Through the use of environmental variables, Diamond attempts to

explain this pattern. Why did the domestication of plants and animals

first occur where and when it did? Why did it not occur in additional

areas that are suitable for the growing of crops or the herding of

animals? Finally, why did some peoples who lived in areas ecologically

suitable for agriculture or herding fail to either develop or acquire

agriculture until modern times? “The underlying reason why this

transition was piecemeal is that food production systems evolved as a

result of the accumulation of many separate decisions about allocating

time and effort” (107). Like

Marvin

Harris and

Gerhard

Lenski before him, Diamond

posits that the transition was not the result of conscious choice but

rather was the result of thousands of small cost/benefit decisions on

the part of individuals over centuries.

Echoing Harris, Diamond posits that many considerations go into this

decision making process, including the simple satisfaction of hunger,

craving for specific foods, a need for protein, fat, or salt. Also

consistent with Harris, Diamond states that people concentrate on foods

that will give them the biggest payoff (taste, calories, and protein) in

return for the least time and effort (107-108). Throughout the

transition, hunting and gathering competed directly with food production

strategies for the time and energy of individuals within the population.

It is only when the cost/benefits of food production outweigh those of

hunting and gathering that people invest more time in that strategy

(109).

What finally gave food production the advantage? It was not that food

production led to an easier life-style. Studies indicate that farmers

and herders spend far more time working for their food than do hunter

and gatherers (109). Nor are they attracted by the abundance, as most

studies indicate that peasants and herders do not eat as well as hunter

and gatherers either. Rather, Diamond posits several factors that led

some hunter and gatherers to gradually make the shift.

The primary factor was perhaps a decline in the availability of wild

foods; with the receding of the glaciers, many prey species became

depleted or extinct. A second factor enumerated by Diamond is an

increasing range and thus availability of some domesticable wild plants.

“For instance, climate changes at the end of the Pleistocene in the

Fertile Crescent greatly expanded the area habitat of wild cereals, of

which huge crops could be harvested in a short time” (110). A third

factor, according to Diamond, was an improvement in the technologies

necessary for food production, specifically tools “for collecting,

processing, and storing wild food” (110). The fourth factor, mentioned

prominently by Diamond, (and Malthus) is the relationship between

population and food production. A final factor noted by Diamond is the

expansion of territory by food producers. This expansion is made

possible by their much greater population densities and certain other

advantages enjoyed by food producers when compared to their hunting and

gathering

neighbors

(112). Diamond calls this relationship autocatalitic,

population and food production rise in tandem—a gradual increase in

population forces people to obtain more food, as food becomes more

plentiful, more children are allowed to survive. Once hunters and

gatherers began to make the switch to food production their increased

yields would impel population growth, thus causing them to produce even

more food, thus beginning the autocatalitic relationship (111). This is

all perfectly in line with the theories of T. Robert Malthus and Ester

Boserup.

While Diamond has not turned over any new ground in his analysis of the

neolithic revolution, he has certainly produced a far richer description

of the domestication process. Diamond explains in interesting detail how

the early domestication of plants could proceed without conscious

thought on the part of early farmers.

Plant domestication, Diamond explains, is the process by which early

farmers selected seeds from plants that were more useful for human

consumption thereby causing changes in the plant’s genetic makeup. But

it is not a one-way process, once humans begin to select certain seeds

over others they are changing the environmental conditions of the plants

themselves, changing the conditions upon which certain plants will

thrive and propagate their seed (123). Plants that produced bigger

seeds, or a more attractive taste for humans, would initially be chosen

in the gathering process and would be those that were first planted in

early gardens (117). Then, the new conditions would favor some of these

seeds over others (123). The conditions of the garden as well as the

unconscious and conscious selection of the farmer over which seeds to

sow the following spring gradually changed the genetic structure of

domesticated plants so that domesticated varieties are often starkly

different than their wild ancestors.

Through this process, Diamond notes, hunters and gatherers domesticated

almost all of the crops that we consume today; not one major new

domesticate has been added since Roman times (128). Further, only a

dozen plant species account for over 80 percent of the world’s annual

crop yields. “With so few crops in the world, all of them domesticated

thousands of years ago, it’s less surprising that many areas of the

world had no wild native plants at all of outstanding potential” (132).

Animal domestication, Diamond explains, is the process by which early

farmers selectively bred animals that were more useful for humans

thereby causing changes in the animal’s genetic makeup. There are 148

wild, large, herbivorous mammals that were available for domestication,

Diamond reports, but only 14 were ever domesticated.

These included the “major five” (sheep, goats, cattle, pig, and horse)

and the “minor nine” (Arabian and Bactrian camel, llama and alpaca,

donkey, reindeer, water buffalo, yak, Bali cattle, and the mithan)

(160-161). Diamond asks: Why did so few of the 148 become domesticated?

Why did so many fail? Because, Diamond answers, not just any wild animal

can be domesticated; to be successful a candidate must possess six

specific characteristics, lack of any one of which would make all

efforts at domestication futile (169).

The first factor required for successful domestication is the diet of

the animal. To be valuable, the animal must consume a diet that

efficiently converts plant life to meat. This plant life also has to be

readily available. A second factor is growth rate, to be worth raising

the animal must grow relatively quickly; animals that take 10 to 20

years to reach mature size represent far too much of an investment for

the average farmer.

A third factor is the problem of breeding—many animals have problems

breeding in captivity, requiring range and privacy that stymies

domestication efforts. A fourth factor is disposition, many animals have

nasty dispositions toward humans and are far too dangerous to

domesticate as a result. A fifth characteristic is tendency to panic;

many species are far too nervous and quick to flight when confronted

with a threat.

The sixth and final characteristic that is necessary for a domestic

relationship with humans regards herd structure. “Almost all species of

domesticated large mammals prove to be ones whose wild ancestors shared

three social characteristics: they live in herds, they maintain a

well-developed dominance hierarchy among herd members; and the herds

occupy overlapping home ranges rather than mutually exclusive

territories” (172).

Eurasian people, befitting their large landmass and environmental

diversity, started out with many more potential domesticates than people

on other continents. Australia and the Americas, you will recall, lost

most of their potential domesticates either through climate change or

the actions of early settlers to these lands. A second factor is that a

far higher percentage of the Eurasian candidates “proved suitable for

domestication” than in Africa, Australia, or the Americas (174-175).

Why did food production first appear in the Fertile Crescent? The

primary advantages of this area is that it enjoyed a Mediterranean

climate of mild, wet winters, and long summers, ideal for crop

production. It also possessed a number of wild ancestors of crops that

were already highly productive and growing in large stands in the wild

(136). A third factor behind the origin of agriculture in the Fertile

Crescent was that it contained four large herbivores that fit the

profile of domestication as well several plants that were suitable for

domestication. “Thanks to this availability of suitable wild mammals and

plants, early people of the Fertile Crescent could quickly assemble a

potent and balanced biological package for intensive food production”

(141-142). Other early originators had similar (though not quite so

varied) biological advantage as well as physical and climatic conditions

suitable for agricultural production. Because of the paucity of wild

plants in the New World that were suitable for domestication, and the

almost complete lack of big herbivores for meat or traction, the coming

of agriculture to these areas was much delayed, and once started was

much slower to develop.

One cannot readily imagine people choosing agriculture over hunting and

gathering in their cost/benefit decision making when their only

available domesticates were sump-weed or squash. In such cases,

agriculture would remain a supplement to the basic hunting and gathering

life style for much longer periods. Diamond posits that the environment

of Eurasia not only

favored

early domestication but also the

spread of agriculture from pristine areas of origin to other societies.

Recall that most societies do not develop agriculture on their own, but

rather receive it through conquest or other cultural contact. The

Eurasian continent has several advantages over Africa and the Americas

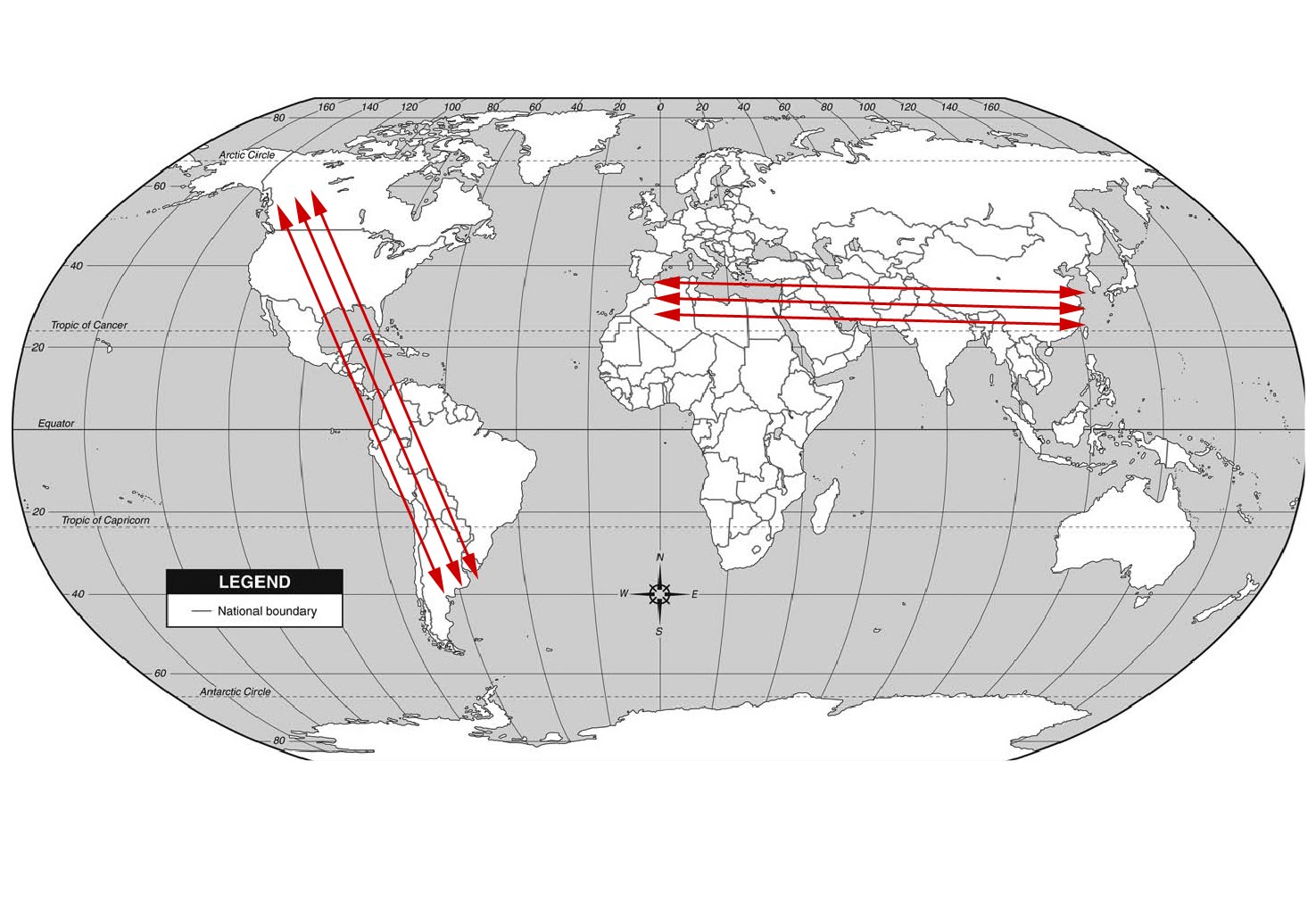

in this regard. The foremost reason for the rapid spread of crops in

Eurasia, according to Diamond, is that the Eurasian continent has an

east-west axis—the bulk of the land mass stretches east to west rather

than north to south. Similar latitudes, Diamond reasons, share the same

seasonal variations, length of days, and often climate (1997, 183).

Thus, plants first cultivated in one area, adapted as they are to such

factors of latitude as growing season and length of day, can easily be

cultivated in areas east or west of the original site.

The axis of the Americas and Africa, on the other hand, are north-south.

Corn that was first domesticated in the Mexican highlands with its long

days and long growing season could not readily spread to areas of the

eastern United States or Canada. To be grown in these new latitudes,

corn had to be genetically modified (or re-domesticated) for these

climates through a very long process of human selection (184). There are

also other geographical barriers to the spread of agriculture, barriers

that will also come into play in the diffusion of other technologies

among societies. Such barriers as desert regions, tropical jungle, and

mountains played a far more prominent role in preventing or slowing down

the spread of agriculture in the Americas and Africa than in Eurasia,

where the barriers are far less formidable.

Diamond calls the acquisition, timing, and spread of agriculture the

ultimate cause of the world inequalities in the 15th century,

but not one of the proximate causes. These proximate or immediate causes

were the superiority of Eurasian technology, particularly their guns,

steel swords and armor; the centralized political governments of

Eurasian nations that allowed the marshaling of armadas of ships and

armies; and the more lethal germs carried by the conquerors. How are

these proximate factors related to agriculture?

Diamond claims that there is an autocatalytic relationship between

intensified food production, population, and societal complexity. First,

food production allows for a sedentary life-style, thus allowing for the

accumulation of possessions as well as the creation of crafts. Second,

intensified food production can be organized to produce a surplus, which

can then be used to support a more complex division of labor as well as

social stratification (285). “When the harvest has been stored, the

farmers’ labor becomes available for a centralized political authority

to harness—in order to build public works advertising state power (such

as the Egyptian pyramids), or to build public works that could feed more

mouths (such as Polynesian Hawaii’s irrigation systems or fishponds), or

to undertake wars of conquest to form larger political entities” (285).

Thus, societal complexity can then stimulate further intensification of

food production.

With population growth, Diamond maintains, wars begin to change their

character as well. With intensified food production and high population

densities, as with states that produce a surplus of food and have a

developed division of

labor, the defeated can be used as slaves or the

defeated society can be forced to pay tribute to the conquerors. During

the hunting and gathering era, where population densities are low,

conflict between groups often meant that the defeated group would merely

move to a new range further removed from the victors. With non-intensive

food production and consequent moderate population level, there is no

place for the defeated to move; in horticultural societies with little

surplus, there is little advantage in keeping the defeated as slaves or

in forcing the defeated area to pay tribute. “Hence the victors have no

use for survivors of a defeated tribe, unless to take the women in

marriage. The defeated men are killed, and their territory may be

occupied by the victors” (291).

The most direct line from the ultimate cause of agriculture to a

proximate cause is the relationship between raising livestock and lethal

germs. “The major killers of humanity throughout our recent

history—smallpox, flu, tuberculosis, malaria, plague, measles, and

cholera—are infectious diseases that evolved from diseases of

animals…”(196-197). Eurasian farmers were exposed to these germs from a

very early

In summary, because food production was far more advanced on the

Eurasian continent, there was great competition, diffusion, and

amalgamation among the states that evolved on this continent. These

states became far larger in population, more resistant to the diseases

carried by domesticates, more sophisticated in terms of technology, and

more centralized politically than the tribes, chiefdoms, and early

states they came into contact with in the New World, the Pacific

Islands, Africa, and Australia. Thus, when worlds collided one barely

survived. Though coming from a tradition based in the biological

sciences and developed almost in isolation from social theory, Diamond’s

work exploring the many relationships between environment, population,

and production—as well as the impact of these relationships on the rest

of the sociocultural system—is perfectly consistent with the principles

of ecological-evolutionary theory.

For a more extensive discussion of Diamond’s work read from his books.

Also see

Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure and Change

to learn how his insights contribute to a fuller understanding

of modern societies.

Diamond, J. 1997. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human

Societies. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Elwell, F. W. 2013. Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure

and Change. Canada: Athabasca University Press.

Lenski, G. 2005. Ecological-Evolutionary Theory: Principles and

Applications. Colorado: Paradigm.

To reference The Implicit Ecological-Evolutionary Theory of Jared

Diamond you should use the following format:

Elwell, Frank W. 2013. "The Implicit Ecological-Evolutionary Theory of

Jared Diamond,” Retrieved August 31, 2013 [use actual date]

http://www.faculty.rsu.edu/~felwell/Theorists/Essays/Elias1.htm

©2013 Frank Elwell, Send comments to felwell at rsu.edu

|

time, thus many developing immunities to the diseases. Though

Eurasians were mainly resistant to these diseases, they remained

carriers. Thus native populations of the Americas, Australia, and

Polynesia were often decimated before guns and steel were used to

subjugate them.

time, thus many developing immunities to the diseases. Though

Eurasians were mainly resistant to these diseases, they remained

carriers. Thus native populations of the Americas, Australia, and

Polynesia were often decimated before guns and steel were used to

subjugate them.