Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure and Change Macrosociology: Four Modern Theorists A Commentary on Malthus" 1798 Essay as Social Theory Great Classical Social Theorists In the Classical Tradition: Modern Social Theorists Dr. Elwell's Professional Page

|

rbert Spencer's Evolutionary

Sociology Robert A. Nisbet [1913-1996] | |

|

Robert Nisbet and the New Totalitarianism

By Frank W. Elwell

Robert Nisbet cites Weber’s assertion of the ongoing

conflict between democracy and bureaucracy: democracy promotes

bureaucracy because such organizations are necessary to provide the

coordination and control so desperately needed by complex society (and

huge populations). Such functions as the administration of justice,

education, voting, and other complex administrative tasks could never be

accomplished without bureaucratic coordination. But while modern

societies are dependent on these organizations, in the long-run

bureaucracy tends to undermine both human freedom and democracy (Nisbet

1975, 54-56). Over time, State bureaucracy becomes resistant to the rule

of elected officials—the bureaucracy is permanent and will always be

there, elected officials are transient. The result, Nisbet asserts, is

that elected officials often engage in

While most office seekers promise to cut bureaucratic

waste and downsize staffs, bureaus and departments, once in office they

never do. The bureaucratization of Western governments primarily comes

from two sources: war and social reform (Nisbet 1975, 59). Nisbet

predicts that this trend as well as the rise in the incidence of

terrorism will continue. The rise in crime and the increasing threat of

terror will cause the U Like C. Wright Mills before him, Nisbet believes that

the military caste of mind increasingly dominates our government. The

threat of terrorism, the decline of civil authority, the breakdown of

family and community structures of authority, all point to the rise of

militarism. In fact, Nisbet asserts that if terrorism continues to

increase in the coming decades as rapidly as it had in the decade

previous to his writing, he could not conceive of representative

democracy surviving. It is not that he predicted that the terrorists

would win, but rather that the U.S. would feel compelled to abandon its

Bill of Rights ((Nisbet 1975, 61-64). As evidence for the rise of

militarism, Nisbet points to the increased incidence and intensity of

war in the 20th century. Also evident is the increase in the

“size, reach, and sheer functional importance of the military” in modern

times. To believe that such an institution growing rapidly in our midst

has not had serious impact on other parts of the sociocultural system—on

domestic and foreign policy, the economy, on civil and cultural life—is

ludicrous (Nisbet 1988, 1). “To imagine that the military’s annual

budget of just under a hundred billion dollars does not have significant

effect upon the economy is of course absurd, and i Also like Mills, Nisbet sees the intellectual class

as being complicit in their support of the military state. Under Wilson

and later Roosevelt, intellectuals were brought into government service

and gave their full support to the centralization of power in the

federal government (and increasingly the executive branch), and to the

militarization Again like Mills and his assertions that power in a

bureaucratized society is increasingly based on manipulation rather than

force, Nisbet is not predicting the evolution of American society into

something akin to Nazi Germany, rather, he sees America rapidly moving

toward “legal and administrative tyranny” (Nisbet 1988, 57). Nisbet sees

power in contemporary America as becoming “invisible,” removed first

from family and community to elective office but now increasingly placed

in the hands of the many State bureaucrats who regulate government,

politics, economy, educational institutions, medical facilities—our The most revolutionary change of the twentieth

century, Nisbet asserts, is that power and authority has been

transferred from the offices of constitutional government to

bureaucracies “brought into being in the name of protection of the

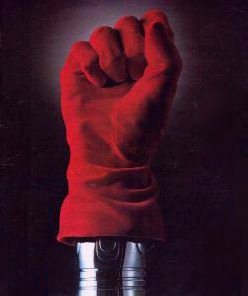

people from their exploiters (Nisbet 1975, 195-196). This “softening” of

power, placing the velvet glove over the iron fist of the State, makes

such power much more difficult to detect or oppose (Nisbet 1975, 223).

“In the name of education, welfare, taxation, safety, health, and the

environment, to mention but a few of the laudable ends involved, the

The quaint old forms and trappings of democracy--elections, supreme courts, Congress, and the Constitution--will remain in place. The traditional names and slogans will continue to be called upon and broadcast; freedom and democracy will continue to be the theme of presidential speeches and editorials. And certain freedoms will reign. “There are, after all, certain freedoms which are like circuses. Their very existence, so long as they are individual and enjoyed chiefly individually as by spectators, diverts men’s minds from the loss of other, more fundamental, social and economic and political rights” (Nisbet 1975, 229). But this, Nisbet asserts, is simply an illusion of freedom, yet another way of softening power. As in the present, political scientists and sociologists will continue to debate the totalitarian hypothesis. But it will be democracy and freedom in a trivial sense, unimportant and subject to “guidance and control” or manipulation by the State (Nisbet 1953, 185; 1975, 229). The first condition for the rise of the totalitarian State is that intermediate groups be severely weakened or destroyed. “We may regard totalitarianism,” Nisbet writes, “as a process of the annihilation of individuality, but, in more fundamental terms, it is the annihilation, first, of those social relationships within which individuality develops. It is not the extermination of individuals that is ultimately desired by totalitarian rulers, for individuals in the largest number are needed by the new order. What is desired is the extermination of those old social relationships which, but for their autonomous existence, must always constitute a barrier to the achievement of the absolute political community” (Nisbet 1953, 179).

The second condition is that the State extend its administrative structure, control, and regulation to all aspects of social life—aspects that used to be the purview of these intermediate groups (Nisbet 1953, 182). Any new groups or associations formed must be subject to the regulation and control of the State. Intermediate groups, he says, become “plural only in number, not in ultimate allegiance of purpose” (Nisbet 1953, 186). And this destruction and cooptation of intermediate organizations is the true horror of totalitarian rule for it destroys the very foundation of identity, individual morality, protection from arbitrary rule, and freedom itself. Intermediate institutions, Nisbet argues, are essential in inspiring individuals to restrain their appetites, to internalize social morality and thus make civil society possible. Intermediate institutions also form the walls that heretofore contained the State’s appetite for power (Nisbet 1975, 74). Therefore, he states, “total political centralization can only lead to social and cultural death” (Nisbet 1953, 187). Nisbet sees th What Nisbet advocates for the cultural disease that

he has so thoroughly described is institutional reform based on the

principles of libertarianism and pluralism. He states that distinctive

institutions—economic, educational, family, religion—must be left as

free as possible from the regulation and dictates of the State. He

advocates a program of decentralization, devolving powers from the

federal government to the states and from the states to local community

organizations. He calls for the strengthening, re-creation, or creation

of viable intermediate associations, groups and communities that can

buffer the effects of the State upon the individual; such groups must

have real functional importance in the allocation of goods and services,

for only then can such groups stimulate solidarity and commitment from

individual members (Nisbet 1975, 278). (This parallels Durkheim’s call

for the establishment of these same types of associations.) He asks us

to give up ou And it is in our power to return, Nisbet believes,

for there is no social problem that is not in our power to correct. “It

is not as though we are dealing with the relentless advance of

senescence in the human being or the course of cancer. Ideas and their

consequences could make an enormous difference in our present spirit.

For whatever it is that gives us torment…it rests upon ideas which are

as much captive to history today as they ever have been. The genius, the

maniac, and the prophet have been responsible for more history than the

multitudes have or ever will. And the power of those beings rests upon

revolutions in ideas and idea systems” (Nisbet 1988, 134-135). For a more extensive discussion of Nisbet's theories refer to Macro Social Theory by Frank W. Elwell. Also see Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure and Change to learn how his insights contribute to a more complete understanding of modern societies.

References:

Elwell, F. W. 2009. Macrosociology: The Study of Sociocultural

Systems. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press.

Elwell, F. W. 2006. Macrosociology: Four Modern Theorists.

Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

Elwell, F. W. 2013. Sociocultural Systems: Principles of Structure and

Change. Alberta: Athabasca University Press.

The Present Age: Progress and Anarchy in Modern America.

New York: Harper Row, 1989.

Robert Nisbet.

1977. The Social Bond. New York: Knopf.

Robert Nisbet.

1975. Twilight of Authority. New York: Oxford University Press.

Robert Nisbet.

1967. The Sociological Tradition. New York: Basic Books.

Robert Nisbet.

1953. The Quest for Community: A Study in the Ethics of Order and

Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press.

To reference Robert Nisbet and the New Totalitarianism you should use

the following format:

Elwell, Frank W. 2013. "Robert Nisbet and the New Totalitarianism,"

Retrieved August 31, 2013 [use actual date]

http://www.faculty.rsu.edu/~felwell/Theorists/Essays/Nisbet1.htm

|

demagoguery and the violation of

form to get their way. Forms are the traditional, legal, or accustomed

ways of government, the respect for office, procedure, law, opposing

parties, consultation and open communication within executive agencies

and between branches of government. “Forms are, above all else, powerful

restraints upon the kinds of passion which are generated so easily in

religion and politics. Few things are more obvious in the recent history

of the United States than the quickened decline of forms in all spheres

of social life, but particularly, and most decisively, in the political”

(Nisbet 1975, 37). The decline of forms has continued well into the 21st

century associated with the extreme partisanship beginning in the early

1980s, as well as the rise of the national security state after 9/11.

This decline, according to Nisbet, is associated with impatience with

the pace of democratic government, and viewing various agencies and

coequal branches as impediments to the will of the executive. Democratic

forms come to be viewed as standing in the way of achieving important

goals. Once these forms are flouted, however, they lose all restraining

force on centralized power (Nisbet 1975, pp. 37-39).

demagoguery and the violation of

form to get their way. Forms are the traditional, legal, or accustomed

ways of government, the respect for office, procedure, law, opposing

parties, consultation and open communication within executive agencies

and between branches of government. “Forms are, above all else, powerful

restraints upon the kinds of passion which are generated so easily in

religion and politics. Few things are more obvious in the recent history

of the United States than the quickened decline of forms in all spheres

of social life, but particularly, and most decisively, in the political”

(Nisbet 1975, 37). The decline of forms has continued well into the 21st

century associated with the extreme partisanship beginning in the early

1980s, as well as the rise of the national security state after 9/11.

This decline, according to Nisbet, is associated with impatience with

the pace of democratic government, and viewing various agencies and

coequal branches as impediments to the will of the executive. Democratic

forms come to be viewed as standing in the way of achieving important

goals. Once these forms are flouted, however, they lose all restraining

force on centralized power (Nisbet 1975, pp. 37-39). nited States and other western countries to

increasingly turn to military forms of government in order to restore

confidence in the ability of government to protect its citizenry. The

rise in crime is predicated upon the rise in anomie as norms and values

fail to be internalized and lose their effectiveness in disciplining

egoistic individuals. The predicted increase in the amount of terrorism

is based on the centralization and enlargement of power in Western (and

other) governments; revolution from disaffected groups is now virtually

impossible. This makes it “probable that the vacuum left by receding

revolutionary hope is being filled by mindless, purposeless terror as an

end in itself” (Nisbet 1975, 61-64, quote on page 63).

nited States and other western countries to

increasingly turn to military forms of government in order to restore

confidence in the ability of government to protect its citizenry. The

rise in crime is predicated upon the rise in anomie as norms and values

fail to be internalized and lose their effectiveness in disciplining

egoistic individuals. The predicted increase in the amount of terrorism

is based on the centralization and enlargement of power in Western (and

other) governments; revolution from disaffected groups is now virtually

impossible. This makes it “probable that the vacuum left by receding

revolutionary hope is being filled by mindless, purposeless terror as an

end in itself” (Nisbet 1975, 61-64, quote on page 63). t may be assumed that

with respect to the military as with any other institution, beginning

with the family, what affects the economic sphere also affects in due

time other spheres of life” (Nisbet 1975, 147-148). (In 2007 the U.S.

military budget is over 625 billion dollars!) By 1988 Nisbet was calling

the U.S. an “imperial power,” likened to Great Britain in the eighteenth

century. Like Mills before him, Nisbet saw the militarism of the federal

government as one of the greatest threats to freedom in this country and

abroad. Nisbet concludes that such a military establishment will

necessarily have a significant and continuous effect upon the entire sociocultural system. The problem of the militarization of power would

not be so critical if we only had to face the increasing centralization

of government and the related decline of intermediate authority, or if

we were only facing increased military and terror threats from abroad.

“But the fact is, both of those conditions are present, and in mounting

intensity, and against them any thought of arresting or reversing the

processes of militarization of society seems rather absurd. The

industrial-academic-labor-military complex President Eisenhower referred

to in his farewell remarks has become vastly greater since his

presidency, and the military’s ascendancy in this complex becomes

greater all the time, though not, as I have noted, without much

assistance from each of the other elements” (Nisbet 1975, 193). The

“military industrial complex” and the “scientific-technological elite”

that President Eisenhower spoke of means that research universities and

institutes, corporations, the military, and government leaders all have

a vested interest in a large military, sophisticated weapons systems,

and war (Nisbet 1988, 24-28). No nation, Nisbet warns, has ever managed

to retain its “representative character” along with a massive military

establishment; the U.S. will not be an exception (Nisbet 1988, 39).

t may be assumed that

with respect to the military as with any other institution, beginning

with the family, what affects the economic sphere also affects in due

time other spheres of life” (Nisbet 1975, 147-148). (In 2007 the U.S.

military budget is over 625 billion dollars!) By 1988 Nisbet was calling

the U.S. an “imperial power,” likened to Great Britain in the eighteenth

century. Like Mills before him, Nisbet saw the militarism of the federal

government as one of the greatest threats to freedom in this country and

abroad. Nisbet concludes that such a military establishment will

necessarily have a significant and continuous effect upon the entire sociocultural system. The problem of the militarization of power would

not be so critical if we only had to face the increasing centralization

of government and the related decline of intermediate authority, or if

we were only facing increased military and terror threats from abroad.

“But the fact is, both of those conditions are present, and in mounting

intensity, and against them any thought of arresting or reversing the

processes of militarization of society seems rather absurd. The

industrial-academic-labor-military complex President Eisenhower referred

to in his farewell remarks has become vastly greater since his

presidency, and the military’s ascendancy in this complex becomes

greater all the time, though not, as I have noted, without much

assistance from each of the other elements” (Nisbet 1975, 193). The

“military industrial complex” and the “scientific-technological elite”

that President Eisenhower spoke of means that research universities and

institutes, corporations, the military, and government leaders all have

a vested interest in a large military, sophisticated weapons systems,

and war (Nisbet 1988, 24-28). No nation, Nisbet warns, has ever managed

to retain its “representative character” along with a massive military

establishment; the U.S. will not be an exception (Nisbet 1988, 39). of that power in World War, Cold War, and increasingly in

its war on terror. Aside from designing the programs, staffing the upper

levels of the bureaucracies, creating the strategies, and setting

foreign and domestic policies, the intellectual creates the slogans and

ideologies that motivate the masses; spin the moralizing and

rationalizations necessary for war, and define the crises and the

strategies of conflict (Nisbet 1975, 190). Few intellectuals have the

independence of mind or the will to oppose either centralization or

militarization. With the notable exception of Marx, the founders of

sociology—Durkheim, Spencer, Weber, and Sumner—were all extremely

skeptical of centralization and the State. But modern practitioners of

the social sciences almost without exception look to the centralization

and enlargement of the State as if it were part of the natural order of sociocultural systems (Nisbet 1975, 249. Again, echoes of Mills in

The Sociological Imagination).

of that power in World War, Cold War, and increasingly in

its war on terror. Aside from designing the programs, staffing the upper

levels of the bureaucracies, creating the strategies, and setting

foreign and domestic policies, the intellectual creates the slogans and

ideologies that motivate the masses; spin the moralizing and

rationalizations necessary for war, and define the crises and the

strategies of conflict (Nisbet 1975, 190). Few intellectuals have the

independence of mind or the will to oppose either centralization or

militarization. With the notable exception of Marx, the founders of

sociology—Durkheim, Spencer, Weber, and Sumner—were all extremely

skeptical of centralization and the State. But modern practitioners of

the social sciences almost without exception look to the centralization

and enlargement of the State as if it were part of the natural order of sociocultural systems (Nisbet 1975, 249. Again, echoes of Mills in

The Sociological Imagination). very

social existence. The reason that this power has become invisible is

two-fold: (1) it is done in the name of humanitarian goals, the

government as protector and friend; and (2) the State manipulates the

media, the educational system, the smallest details of life so that the

will of the State becomes internalized by the individual (Nisbet 1975,

195-197). “The greatest power,” Nisbet asserts, “is that which shapes

not merely individual conduct but also the mind behind the conduct.

Power that can, through technological or other means, penetrate the

recesses of culture, of the smaller unions of social life, and then of

the mind itself, is manifestly more dangerous to human freedom than the

kind of power that for all its physical brutality, reaches only the

body” (Nisbet 1975, 226-227).

very

social existence. The reason that this power has become invisible is

two-fold: (1) it is done in the name of humanitarian goals, the

government as protector and friend; and (2) the State manipulates the

media, the educational system, the smallest details of life so that the

will of the State becomes internalized by the individual (Nisbet 1975,

195-197). “The greatest power,” Nisbet asserts, “is that which shapes

not merely individual conduct but also the mind behind the conduct.

Power that can, through technological or other means, penetrate the

recesses of culture, of the smaller unions of social life, and then of

the mind itself, is manifestly more dangerous to human freedom than the

kind of power that for all its physical brutality, reaches only the

body” (Nisbet 1975, 226-227). new

despotism confronts us at every turn” (Nisbet 1975, 197). The new

totalitarianism is not based on terror or external force, although the

police powers of the state ultimately undergird its authority. Human

organization that depends on the constant use of force and intimidation

to discipline its members is extremely inefficient and ultimately

ineffective. A system based solely on force must expend too much energy

policing its members; it stifles initiative, and it provides an obvious

target for rallying opposition. Rather, the new totalitarianism is

founded upon the ever more sophisticated methods of control given us by

science (including social science) and technology, based on

manipulation. Government power is far greater today than it ever was,

Nisbet asserts, but it is far more indirect, impersonal, and based on

manipulation rather than brute force (Nisbet 1975, 223). While the old

totalitarianism is based on force and terror, the new totalitarianism is

based on the art of manipulation. The bureaucratic growth of the State

to absolute power and authority over the masses is even more absolute

than old forms of totalitarianism because it encompasses humanitarian

concerns (Nisbet 1988, 61). Using technologies of mass media,

advertising, and propaganda, the goal of the new totalitarian State is

to control its population, to get them to mobilize, believe, and act in

accordance with the wishes of the State.

new

despotism confronts us at every turn” (Nisbet 1975, 197). The new

totalitarianism is not based on terror or external force, although the

police powers of the state ultimately undergird its authority. Human

organization that depends on the constant use of force and intimidation

to discipline its members is extremely inefficient and ultimately

ineffective. A system based solely on force must expend too much energy

policing its members; it stifles initiative, and it provides an obvious

target for rallying opposition. Rather, the new totalitarianism is

founded upon the ever more sophisticated methods of control given us by

science (including social science) and technology, based on

manipulation. Government power is far greater today than it ever was,

Nisbet asserts, but it is far more indirect, impersonal, and based on

manipulation rather than brute force (Nisbet 1975, 223). While the old

totalitarianism is based on force and terror, the new totalitarianism is

based on the art of manipulation. The bureaucratic growth of the State

to absolute power and authority over the masses is even more absolute

than old forms of totalitarianism because it encompasses humanitarian

concerns (Nisbet 1988, 61). Using technologies of mass media,

advertising, and propaganda, the goal of the new totalitarian State is

to control its population, to get them to mobilize, believe, and act in

accordance with the wishes of the State.

e trend toward militarism,

centralization, and the weakening of primary groups as inexorable and is

skeptical that there will be any significant and long lasting reversal

of these trends any time soon. However, he does offer some hope. Echoing

Weber, he states that a charismatic—a prophet, a genius, or a

maniac—might well stop or even reverse the trends (Nisbet 1975, 233).

e trend toward militarism,

centralization, and the weakening of primary groups as inexorable and is

skeptical that there will be any significant and long lasting reversal

of these trends any time soon. However, he does offer some hope. Echoing

Weber, he states that a charismatic—a prophet, a genius, or a

maniac—might well stop or even reverse the trends (Nisbet 1975, 233). r passion for equality and recognize that hierarchy is part

of the social bond and essential for social order as well as the

transmission of our culture across generations. He calls for a

recommitment to tradition, to abandon attempts to regulate every aspect

of life through formal law and administrative regulation and rely upon

custom and folkway in their stead. “Pluralist society is free society

exactly in proportion to its ability to protect as large a domain as

possible that is governed by the informal, spontaneous, custom-derived,

and tradition-sanctioned habits of mind rather than by the dictates,

however rationalized, of government and judiciary” (Nisbet 1975, 240).

We are becoming a nation of lawyers; our relationships are increasingly

adversarial and defined by legal code or administrative decree. But

freedom, liberty, and authority are all rooted in tradition and in

primary group association, and it is to this foundation that we must

return.

r passion for equality and recognize that hierarchy is part

of the social bond and essential for social order as well as the

transmission of our culture across generations. He calls for a

recommitment to tradition, to abandon attempts to regulate every aspect

of life through formal law and administrative regulation and rely upon

custom and folkway in their stead. “Pluralist society is free society

exactly in proportion to its ability to protect as large a domain as

possible that is governed by the informal, spontaneous, custom-derived,

and tradition-sanctioned habits of mind rather than by the dictates,

however rationalized, of government and judiciary” (Nisbet 1975, 240).

We are becoming a nation of lawyers; our relationships are increasingly

adversarial and defined by legal code or administrative decree. But

freedom, liberty, and authority are all rooted in tradition and in

primary group association, and it is to this foundation that we must

return.